The Ninth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty

King Amenhotep III

Amenhotep III, also known as Amenhotep the Magnificent, was the ninth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. According to different authors, he ruled Egypt from June 1386 to 1349 BC, or from June 1388 BC to December 1351 BC/1350 BC, after his father Thutmose IV died. Amenhotep III was

Thutmose's son by a minor wife, Mutemwiya.

His reign was a period of unprecedented prosperity and artistic splendour, when Egypt reached the peak of its artistic and international power. When he died in the 38th or 39th year of his reign, his son initially ruled as Amenhotep IV, but then changed his own royal name to Akhenaten.

Amenhotep III was the father of two sons with his Great Royal Wife Tiye, a queen who could be considered as the progenitor of monotheism through her first son, Crown Prince Thutmose, who predeceased his father, and her second son, Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaten, who ultimately succeeded Amenhotep III to the throne. Amenhotep III also may have been the father of a third child - called Smenkhkare, who later would succeed Akhenaten, briefly rule Egypt as pharaoh, and who is thought to have been a woman.

Amenhotep III and Tiye may also have had four daughters: Sitamun, Henuttaneb, Isis or Iset, and Nebetah. They appear frequently on statues and reliefs during the reign of their father and also are represented by smaller objects - with the exception of Nebetah. Nebetah is attested only once in the known historical records on a colossal limestone group of statues from Medinet Habu.

King Amenhotep III Family - His wives and children

The son of the future Thutmose IV (the son of Amenhotep II) and a minor wife Mutemwiya, Amenhotep was born around 1388 BC. He was a member of the Thutmosid family that had ruled Egypt for almost 150 years since the reign of Thutmose I.

Vase in the Louvre with the names Amenohotep III and Tiye written in the cartouches on the left, (and Tiye's on the right).

Amenhotep III had eight wives:

Queen Tiye : Eleven scarabs record the excavation of an artificial lake he had built for his royal wife, Queen Tiye, in his eleventh regnal year.

Two sons :

Amenhotep III was the father of two sons with his Great Royal Wife Tiye, a queen who could be considered as the progenitor of monotheism through her first son, Crown Prince Thutmose, who predeceased his father, and her second son, Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaten, who ultimately succeeded Amenhotep III to the throne. Amenhotep III also may have been the father of a third child - called Smenkhkare, who later would succeed Akhenaten, briefly rule Egypt as pharaoh, and who is thought to have been a woman.

Daughters and Wives ????

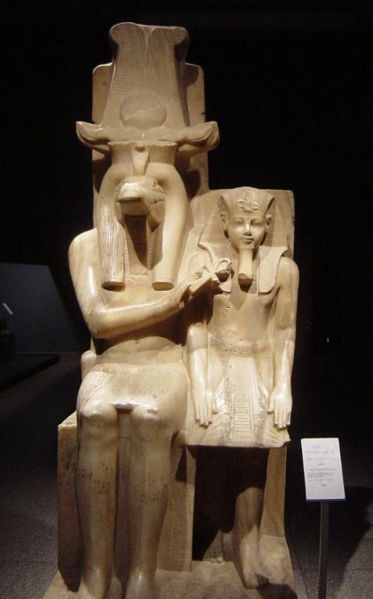

Monumental statue of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiy, along with their daughters

Amenhotep III and Tiye may also have had four daughters: Sitamun, Henuttaneb, Isis or Iset, and Nebetah. They appear frequently on statues and reliefs during the reign of their father and also are represented by smaller objects - with the exception of Nebetah. Nebetah is attested only once in the known historical records on a colossal limestone group of statues from Medinet Habu This huge sculpture, that is seven meters high, shows Amenhotep III and Tiye seated side by side, "with three of their daughters standing in front of the throne - Henuttaneb, the largest and best preserved, in the centre; Nebetah on the right; and another, whose name is destroyed, on the left."

Amenhotep III elevated two of his four daughters - Sitamun and Isis - to the office of "great royal wife" during the last decade of his reign. Evidence that Sitamun already was promoted to this office by Year 30 of his reign, is known from jar-label inscriptions uncovered from the royal palace at Malkata. It should be noted that Egypt's theological paradigm encouraged a male pharaoh to accept royal women from several different generations as wives to strengthen the chances of his offspring succeeding him. The goddess Hathor herself was related to Ra as first the mother and later wife and daughter of the god when he rose to prominence in the pantheon of the Ancient Egyptian religion. Hence, Amenhotep III's marriage to his two daughters should not be considered unlikely based on contemporary views of marriage.

Five girls are attested daughters according to specialists:

01-Sitamon (or Satamon or Satamun - SAt Jmn - Daughter of Amon) who is the eldest daughter.

Fragment of a relief showing princess Sitamun (Sitamen). From the mortuary temple of Amenhotep II at Thebes, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Sitamun (also Sitamen, Satamun; c. 1370 BCE–unknown) was an Ancient Egyptian princess and queen consort during the 18th dynasty. Sitamun is considered to be the eldest daughter of Pharaoh Amenhotep III and his Great Royal Wife Tiye. She was later married to her father around Year 30 of Amenhotep III's reign. The belief that Sitamun was a daughter of Amenhotep and Tiye is based on the presence of objects found in the tomb of Yuya and Thuya, Queen Tiye's parents,[3] especially a chair bearing her title as the king's daughter.

02- Iset (daughter of Amenhotep III):

Iset or Aset was a Princess of Egypt. Isis was one of the daughters of Ancient Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III of the 18th dynasty and his Great Royal Wife Tiye. She was a sister of Akhenaten. Iset's other brother was Crown Prince Thutmose.

Her name is the original Egyptian version of the name Isis. It is likely she was the royal couple's second daughter (after Sitamun). She became her father's wife in Year 34 of Amenhotep's reign, around Amenhotep's second sed festival.

She appears in the temple at Soleb with her parents and her sister Henuttaneb, and on a carnelian plaque (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City) with Henuttaneb, before their parents. A box found in Gurob and a pair of kohl-tubes probably belong to her.

After the death of her father she is not mentioned again.

03-Henuttaneb : Henuttaneb was an Egyptian princess:

Colossal statues (JE 33906), between her parents, Amenhotep III and Tiye, there stands Henuttaneb, Egyptian Museum (Cairo).

Henuttaneb was one of the daughters of Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III of the 18th dynasty and his Great Royal Wife, Queen Tiye. She was a sister of Pharaoh Akhenaten. She also had several more siblings - one other brother and several sisters.

Henuttaneb's name means Lady of All Lands and was also frequently used as a title for queens. She was the third daughter of her parents (after Sitamun and Isis, also called Iset).

Henuttaneb is shown on a colossal statue from Medinet Habu. his huge seven metre high sculpture shows Amenhotep III and Tiye seated side by side, "with three of their daughters standing in front of the throne--Henuttaneb, the largest and best preserved, in the centre; Nebetah on the right; and another, whose name is destroyed, on the left" She also appears in the temple at Soleb and on a carnelian plaque (with her sister Iset, before their parents). Her name appears on three faience fragments.

It is unclear whether Henuttaneb was elevated to the rank of queen like Sitamun and Iset. She is nowhere mentioned as King's Wife, but on the aforementioned carnelian plaque her name is enclosed in a cartouche, a privilege which only kings and their wives were entitled to. After the death of her father she is not mentioned again

04-Nebetah is the 4th daughter Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III of the 18th dynasty

Nebetah was one of the daughters of Ancient Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III of the 18th dynasty and his Great Royal Wife Tiye. She was a younger sister of Akhenaten.

Nebetah's name means Lady of the Palace. Her name, like that of her elder sister Henuttaneb was also frequently used as a title for queens. She was possibly one of the youngest of the royal couple's children, since she doesn't appear on monuments on which her elder sisters do. She is shown on a colossal statue from Medinet Habu. This huge seven metre high sculpture shows Amenhotep III and Tiye seated side by side, "with three of their daughters standing in front of the throne--Henuttaneb, the largest and best preserved, in the centre; Nebetah on the right; and another, whose name is destroyed, on the left."

06-Beketaten - 5th daughter Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III of the 18th dynasty

Queen Tiye's sculptor Yuti finishes a statue of Princess Baketaten. Amarna tomb of Huya.

Beketaten (14th century BCE) was an Ancient Egyptian princess of the 18th dynasty. Beketaten is considered to be the youngest daughter of Pharaoh Amenhotep III and his Great Royal Wife Tiye, thus the sister of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Her name means "Handmaid of Aten".

Beketaten is mainly known from the tomb of Huya, the steward of Queen Tiye in Amarna.

Beketaten is shown with Queen Tiye in two separate banquet scenes. Queen Tiye is shown seated opposite Pharaoh Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti. In one scene Beketaten is shown seated on a small chair next to her mother Tiye, and in the other banquet scene Beketaten is shown standing next to Tiye. On the east wall of Huya's tomb Akhenaten is shown leading his mother Tiye to a temple. They are accompanied by the Beketaten as they enter the temple.

The lintel on the North Wall shows a depiction of the two royal families. On the right side Amenhotep III is shown seated opposite Queen Tiye who is accompanied by the princess Beketaten. Three female attendants are shown behind Tiye

Amenhotep III is known to have married several foreign women:

Gilukhepa, the daughter of Shuttarna II of Mitanni, in the tenth year of his reign.

Tadukhepa, the daughter of his ally Tushratta of Mitanni, Around Year 36 of his reign.

A daughter of Kurigalzu, king of Babylon.

A daughter of Kadashman-Enlil, king of Babylon.

A daughter of Tarhundaradu, ruler of Arzawa.

A daughter of the ruler of Ammia (in modern Syria)

Life

Colossal granite head of Amenhotep III, British Museum.

Amenhotep III enjoyed the distinction of having the most surviving statues of any Egyptian pharaoh, with over 250 of his statues having been discovered and identified. Since these statues span his entire life, they provide a series of portraits covering the entire length of his reign.

Another striking characteristic of Amenhotep III's reign is the series of over 200 large commemorative stone scarabs that have been discovered over a large geographic area ranging from Syria (Ras Shamra) through to Soleb in Nubia. Their lengthy inscribed texts extol the accomplishments of the pharaoh. For instance, 123 of these commemorative scarabs record the large number of lions (either 102 or 110 depending on the reading) that Amenhotep III killed "with his own arrows" from his first regnal year up to his tenth year. Similarly, five other scarabs state that the foreign princess who would become a wife to him, Gilukhepa, arrived in Egypt with a retinue of 317 women. She was the first of many such princesses who would enter the pharaoh's household.

Amenhotep appears to have been crowned while still a child, perhaps between the ages of 6 and 12. It is likely that a regent acted for him if he was made pharaoh at that early age. He married Tiye two years later and she lived twelve years after his death. His lengthy reign was a period of unprecedented prosperity and artistic splendour, when Egypt reached the peak of her artistic and international power. Proof of this is shown by the diplomatic correspondence from the rulers of Assyria, Mitanni, Babylon, and Hatti which is preserved in the archive of Amarna Letters; these letters document frequent requests by these rulers for gold and numerous other gifts from the pharaoh. The letters cover the period from Year 30 of Amenhotep III until at least the end of Akhenaten's reign. In one famous correspondence - Amarna letter EA 4 - Amenhotep III is quoted by the Babylonian king Kadashman-Enlil I in firmly rejecting the latter's entreaty to marry one of this pharaoh's daughters --

"From time immemorial, no daughter of the king of Egy[pt] is given to anyone."

Amenhotep III's refusal to allow one of his daughters to be married to the Babylonian monarch may indeed be connected with Egyptian traditional royal practices that could provide a claim upon the throne through marriage to a royal princess, or, it be viewed as a shrewd attempt on his part to enhance Egypt's prestige over those of her neighbors in the international world.

The pharaoh's reign was relatively peaceful and uneventful. The only recorded military activity by the king is commemorated by three rock-carved stelas from his fifth year found near Aswan and Sai Island in Nubia. The official account of Amenhotep III's military victory emphasizes his martial prowess with the typical hyperbole used by all pharaohs.

Amenhotep III celebrated three Jubilee Sed festivals, in his Year 30, Year 34, and Year 37 respectively at his Malkata summer palace in Western Thebes. The palace, called Per-Hay or "House of Rejoicing" in ancient times, comprised a temple of Amun and a festival hall built especially for this occasion. One of the king's most popular epithets was Aten-tjehen which means "the Dazzling Sun Disk"; it appears in his titulary at Luxor temple and, more frequently, was used as the name for one of his palaces as well as the Year 11 royal barge, and denotes a company of men in Amenhotep's army.

There is a myth on the divine birth of Amenhotep III which is depicted in the Luxor Temple. In this myth, Amenhotep III is conceived by Amun which has gone to Mutemwiya in form of Thutmosis IV

Proposed co-regency by Akhenaten

There is currently no conclusive evidence of a co-regency between Amenhotep III and his son, Akhenaten. A letter from the Amarna palace archives dated to Year 2—rather than Year 12—of Akhenaten's reign from the Mitannian king, Tushratta, (Amarna letter EA 27) preserves a complaint about the fact that Akhenaten did not honor his father's promise to forward Tushratta statues made of solid gold as part of a marriage dowry for sending his daughter, Tadukhepa, into the pharaoh's household. This correspondence implies that if any co-regency occurred between Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, it lasted no more than a year. Lawrence Berman observes in a 1998 biography of Amenhotep III that,

"It is significant that the proponents of the coregency theory have tended to be art historians [e.g., Raymond Johnson], whereas historians [such as Donald Redford and William Murnane] have largely remained unconvinced. Recognizing that the problem admits no easy solution, the present writer has gradually come to believe that it is unnecessary to propose a coregency to explain the production of art in the reign of Amenhotep III. Rather the perceived problems appear to derive from the interpretation of mortuary objects."

In February 2014, Egyptian Ministry for Antiquities announced what it called 'definitive evidence' that Akhenaten shared power with his father for at least 8 years, based on findings from the tomb of Vizier Amenhotep-Huy. The tomb is being studied by a multi-national team led by the Instituto de Estudios del Antiguo Egipto de Madrid and Dr Martin Valentin. The evidence consists of the cartouches of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten being carved side by side but this may only suggest that Amenhotep III had chosen his only surviving son Akhenaten to succeed him since there are no objects or inscriptions known to name and give the same regnal dates for both kings.

The Egyptologist Peter Dorman also rejects any co-regency between these two kings, based on the archaeological evidence from the tomb of Kheruef.

Monuments

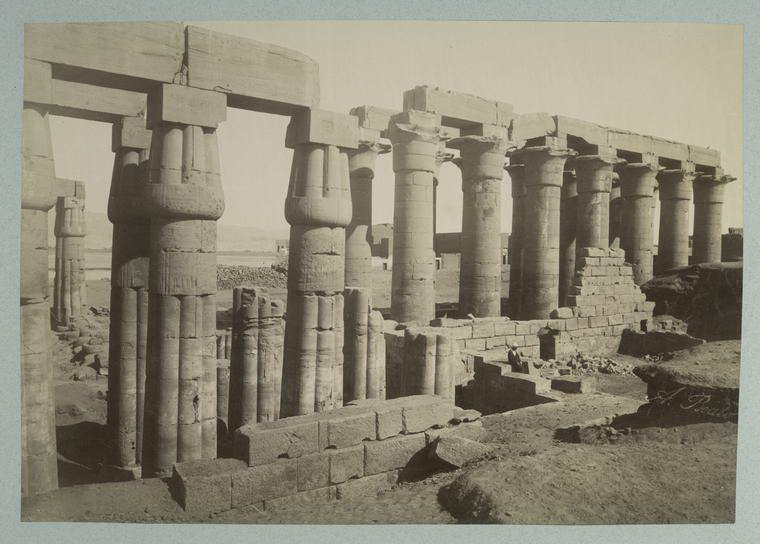

Amenhotep III built extensively at the temple of Karnak including the Luxor temple which consisted of two pylons, a colonnade behind the new temple entrance, and a new temple to the goddess Ma'at. Amenhotep III dismantled the fourth pylon of the Temple of Amun at Karnak to construct a new pylon - the third pylon - and created a new entrance to this structure where he erected "two rows of columns with open papyrus capitals" down the centre of this newly formed forecourt.

The forecourt between the third and fourth pylons of Egypt, sometimes called an obelisk court, was also decorated with scenes of the sacred barque of the deities Amun, Mut, and Khonsu being carried in funerary boats. The king also started work on the Tenth pylon at the Temple of Amun there. Amenhotep III's first recorded act as king - in his Years 1 and 2 - was to open new limestone quarries at Tura, just south of Cairo and at Dayr al-Barsha in Middle Egypt in order to herald his great building projects. He oversaw construction of another temple to Ma'at at Luxor and virtually covered Nubia with numerous monuments.

His enormous mortuary temple on the west bank of the Nile was, in its day, the largest religious complex in Thebes, but unfortunately, the king chose to build it too close to the floodplain and less than two hundred years later, it stood in ruins. Much of the masonry was purloined by Merneptah and later pharaohs for their own construction projects.

The Colossi of Memnon

The Colossi of Memnon - two massive stone statues, eighteen meters high, of Amenhotep that stood at the gateway of his mortuary temple - are the only elements of the complex that remained standing. Amenhotep III also built the Third Pylon at Karnak and erected 600 statues of the goddess Sekhmet in the Temple of Mut, south of Karnak. Some of the most magnificent statues of New Kingdom Egypt date to his reign "such as the two outstanding couchant rose granite lions originally set before the temple at Soleb in Nubia" as well as a large series of royal sculptures. Several beautiful black granite seated statues of Amenhotep wearing the nemes headress have come from excavations behind the Colossi of Memnon as well as from Tanis in the Delta.

Luxor Temple of Amenhotep III

One of the most stunning finds of royal statues dating to his reign was made as recently as 1989 in the courtyard of Amenhotep III's colonnade of the Temple of Luxor where a cache of statues was found, including a 6 feet (1.8 m)-high pink quartzite statue of the king wearing the Double Crown found in near-perfect condition. It was mounted on a sled, and may have been a cult statue. The only damage it had sustained was that the name of the god Amun had been hacked out wherever it appeared in the pharaoh's cartouche, clearly done as part of the systematic effort to eliminate any mention of this god during the reign of his successor, Akhenaton.

Amenhotep III and Sobek, from Dahamsha, now in the Luxor Museum

Sobek (also called Sebek, Sochet, Sobk, and Sobki), in Greek, Suchos (Σοῦχος) and from Latin Suchus, was an ancient Egyptian deity with a complex and fluid nature. He is associated with the Nile crocodile and is either represented in its form or as a human with a crocodile head. Sobek was also associated with pharaonic power, fertility, and military prowess, but served additionally as a protective deity with apotropaic qualities, invoked particularly for protection against the dangers presented by the Nile river.

Final Years

Reliefs from the wall of the temple of Soleb in Nubia and scenes from the Theban tomb of Kheruef, Steward of the King's Great Wife, Tiye, depict Amenhotep as a visibly weak and sick figure. Scientists believe that in his final years he suffered from arthritis and became obese. It has generally been assumed by some scholars that Amenhotep requested and received from his father-in-law Tushratta of Mitanni, a statue of Ishtar of Nineveh--a healing goddess - in order to cure him of his various ailments which included painful abscesses in his teeth.

A forensic examination of his mummy shows that he was probably in constant pain during his final years due to his worn, and cavity-pitted teeth. However, more recent analysis of Amarna letter EA 23 by William L. Moran, which recounts the dispatch of the statue of the goddess to Thebes, does not support this popular theory. The arrival of the statue is known to have coincided with Amenhotep III's marriage with Tadukhepa, Tushratta's daughter, in the pharaoh's 36th year; letter EA 23's arrival in Egypt is dated to "regnal year 36, the fourth month of winter, day 1" of his reign. Furthermore, Tushratta never mentions in EA 23 that the statue's dispatch was meant to heal Amenhotep from his maladies.

The Stela of Amenophis III. back:raised by Merenptah (1213 - 1203 a. C.) Egyptian Museum.

Death:

Amenhotep III's highest attested reign date comes from a pair of Year 38 wine jar-label dockets from Malkata; though he may have lived briefly into an unrecorded 39th Year and died before the wine harvest for that year arrived.

Amenhotep III was buried in the Western Valley of the Valley of the Kings, in Tomb WV22. Sometime during the Third Intermediate Period his mummy was moved from this tomb and was placed in a side-chamber of KV35 along with several other pharaohs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth dynasties where it lay until discovered by Victor Loret in 1898.

An examination of his mummy by the Australian anatomist Grafton Elliot Smith concluded that the pharaoh was aged between forty and fifty years old at death. His chief wife, Tiye, is known to have outlived him for at least twelve years as she is mentioned in several Amarna letters dated from her son's reign as well as depicted at a dinner table with Akhenaten and his royal family in scenes from the tomb of Huya, which were made during Year 9 and Year 12 of her son's reign.

When Amenhotep III died, he left behind a country that was at the very height of its power and influence, commanding immense respect in the international world; however, he also bequeathed an Egypt that was wedded to its traditional political and religious certainties under the Amun priesthood.

The resulting upheavals from his son Akhenaten's reforming zeal would shake these old certainties to their very foundations and bring forth the central question of whether a pharaoh was more powerful than the existing domestic order as represented by the Amun priests and their numerous temple estates. Akhenaten even moved the capital away from the city of Thebes in an effort to break the influence of that powerful temple and assert his own preferred choice of deities, the Aten. Akhenaten moved the Egyptian capital to the site known today as Amarna (though originally known as Akhetaten, 'Horizon of Aten'), and eventually suppressed the worship of Amun.

Mummy of Amenhotep III

Tomb WV22 - Resting place of one of the rulers of Egypt's New Kingdom, Amenhotep III

Tomb WV22, in the Western arm of the Valley of the Kings, was used as the resting place of one of the rulers of Egypt's New Kingdom, Amenhotep III. The tomb is unique in that it has two subsidiary burial chambers for the pharaoh's wives Tiye and Sitamen (who was also his daughter).

The tombs layout and decoration follow the tombs of the kings predecessors Amenhotep II and Thutmoses IV however the decoration is much finer in quality.

It was officially discovered by Prosper Jollois and Édouard de Villiers du Terrage, engineers with Napoleon's expedition to Egypt in August 1799, but had probably been open for some time before that. Subsequently someone removed images of the pharaoh's head in several places, which can be seen today in the Louvre.

The tomb was officially cleared by Howard Carter in the early twentieth century. Since 1989, a Japanese team from Waseda University led by Sakuji Yoshimura and Jiro Kondo has been working for excavation as well as conservation. The sarcophagus is missing from the tomb.

Credit Text and Photo Wikipedia & Various documents on Egypt

_(1904)_-_front_edited_-_TIMEA.jpg/800px-The_Stela_of_Amenophis_III%2C_raised_by_Merneptah_and_bearing_the_earliest_mention_of_Israel_--Cairo%2C_Egypt._(14)_(1904)_-_front_edited_-_TIMEA.jpg)

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire